Yo, Jan Nimmo, Glasgow, Escocia, quiero saber dónde está Bernardo Flores Alcaraz. Digital Art: Jan Nimmo ©

Bernardo Flores Alcaráz is from the small town of San Juan de las Flores in Atoyac, Guerrero, Mexico. Berardo is nicknamed “Cochiloco” and at the tie of his disappearances, was involved in student politics at the Normalista teacher training college, “Raúl Isidro Burgos”, in Ayotzinapa, Tixtla. His grandfather describes how Bernardo likes to help out his father, Nardo, in the milpa (a traditional smallholding where beans and corn are grown). The family grows coffee. He and another of the 43 normalista students, Cutberto Ortiz Ramos, who were disappeared in Iguala, were descendents of Lucio Cabañas Barrientos, “The Tiger of Atoyac”, founder of the Partido de los Pobres (The Party of the Poor). He campaigned for justice and education for the poor and his role model was Emiliano Zapata.

Like his two descendents Cabañas picked coffee and attended the Rural Normalista School Raul Isidro Burgos in Ayotzinapa. He became a teacher and politically active. It was in the Sierra de Atoyac where he founded his anti-poverty guerrilla movement. He was killed by the Mexican army in 1974 after Cabañas’ people had kidnapped the senator and future president of the State of Guerrero, Rubén Figueroa. Lucio Cabañas has become an iconic figure for social justice movements in Mexico and beyond. His wife, social activist Isabel Nava Alaya was murdered in 2011.

I have included an image of Lucio Cabañas in the portrait of Bernardo, along with the lyrics of a corrido (a popular narrative song) about Cabañas, El Tigre de Atoyac (The Jaguar of Atoyac). There is also a tigre, or jaguar, mask from Guerrero, and the spots at the bottom corner are the spots made by dipping bottles into ash to make the jaguar spots on the ritual dance costumes of Guerrero. The target represents how anyone involved in trying to change the lot of the poor in Guerrero, whether historically, by taking up arms, or today by simply wanting to educate communities, becomes a target. I have used targets in some of the other portraits as I believe that anyone wishing to bring about social change through education, through journalism or through speaking out via social networks or non-violent protest, is now a target in Mexico.

Barnardo, nicknamed “Cochiloco”

Lucio Cabañas Barrientos (taken from the digital newspaper El Amanecer de Chihuahua).

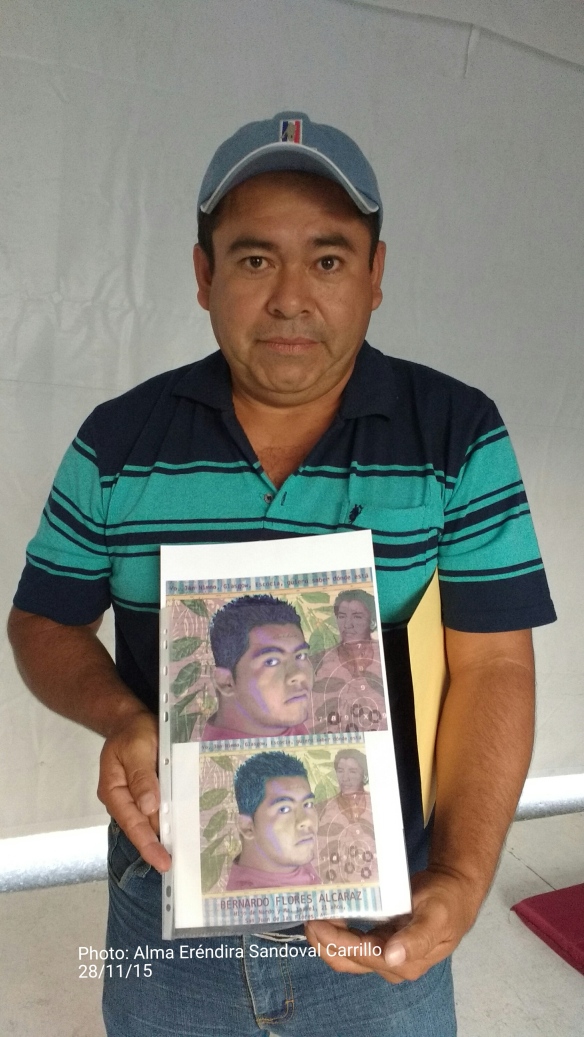

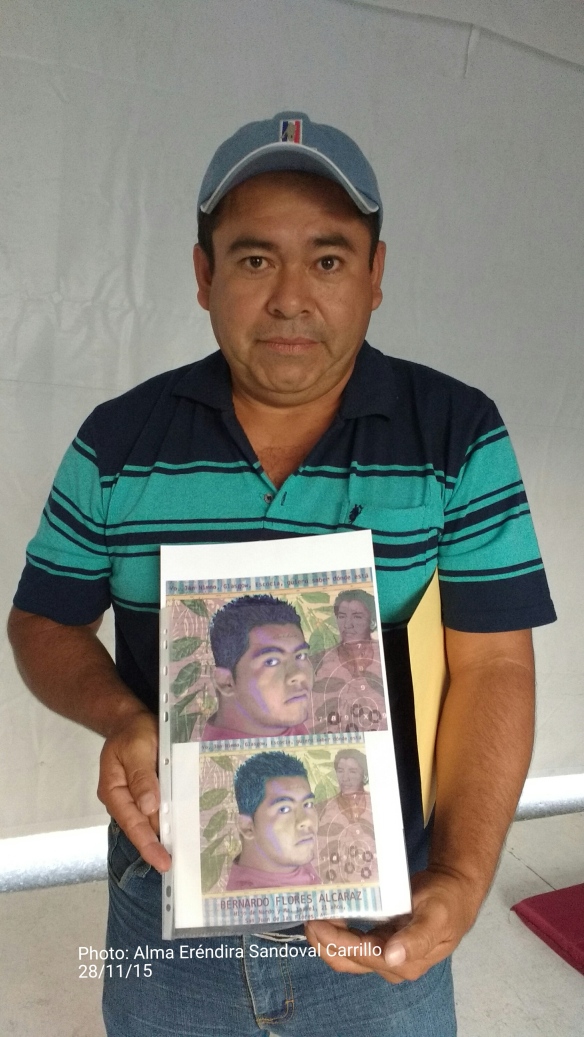

Nardo Flores with the portrait of his son, Bernardo. Photo: Eréndira Sandoval Carrillo.

EL TIGRE DE ATOYAC

El veintisiete de junio

del año setenta y cuatro,

subieron los federales

a la sierra de Atoyac,

buscando a Lucio Cabañas

queriéndolo asesinar.

Lucio Cabañas Barrientos

el rebelde guerrillero

es un tigre muy valiente

que no se liaron el cuero,

secuestra a los millonarios

y no le teme al gobierno.

Gritaba Lucio Cabañas:

De esta sierra ya no salen,

cuídense mis compañeros

ahí vienen los federales,

aviéntense pecho a tierra

allí entre los matorrales.

En la sierra San Vicente

se formó la balacera,

se oían las metralladoras

también los tanques de guerra,

se oían varios cañonazos

en el fondo de la sierra.

Andaban diez mil soldados

de la fuerza federal,

tenían la sierra sitiada

no se podía caminar,

buscaban a Figueroa

queriéndolo rescatar.

Ya con ésta me despido

ya me voy a separar,

¡vivan los hombres valientes

que no se saben rajar!

¡que viva Lucio Cabañas

en la sierra de Atoyac!

Los Valentes (listen to them sing here)

THE JAGUAR OF ATOYAC

On the 26th of June

of the year 1974,

the soldiers went up

to the Sierra de Atoyac,

searching for Lucio Cabañas

who they were wanting to kill.

Lucio Cabañas Barrientos

a rebel guerrilla

Is a valiant tiger

who couldn’t be held back

who kidnaps millionaires

and isn’t afraid of the Government

Cried Lucio Cabañas:

We’ll not leave this sierra,

take care compañeros

here come the soldiers,

crawling on their stomachs,

advancing through the undergrowth.

In the Sierra San Vicente

there was a gunfight

you could hear machine gun fire

and also the tanks of war,

you could hear the cannonades

deep in the heart of the sierra.

Ten thousand soldiers were mobilised

from the federal forces,

they had the sierra surrounded

so no-one could move,

they were looking for Figueroa

who they wanted to rescue.

With this I say farewell

Now I will take my leave,

Long live brave men

that won’t be broken

Long live Lucio Cabañas

in the Sierra de Atoyac!